Gord Made The Ship Famous, John Tells The Stories Of The People

By John Swartz

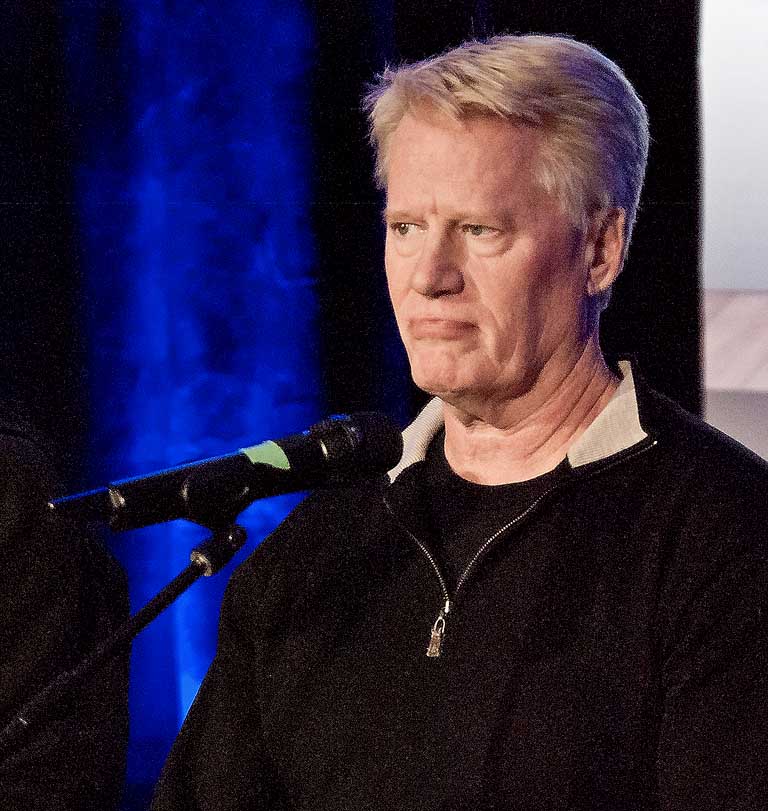

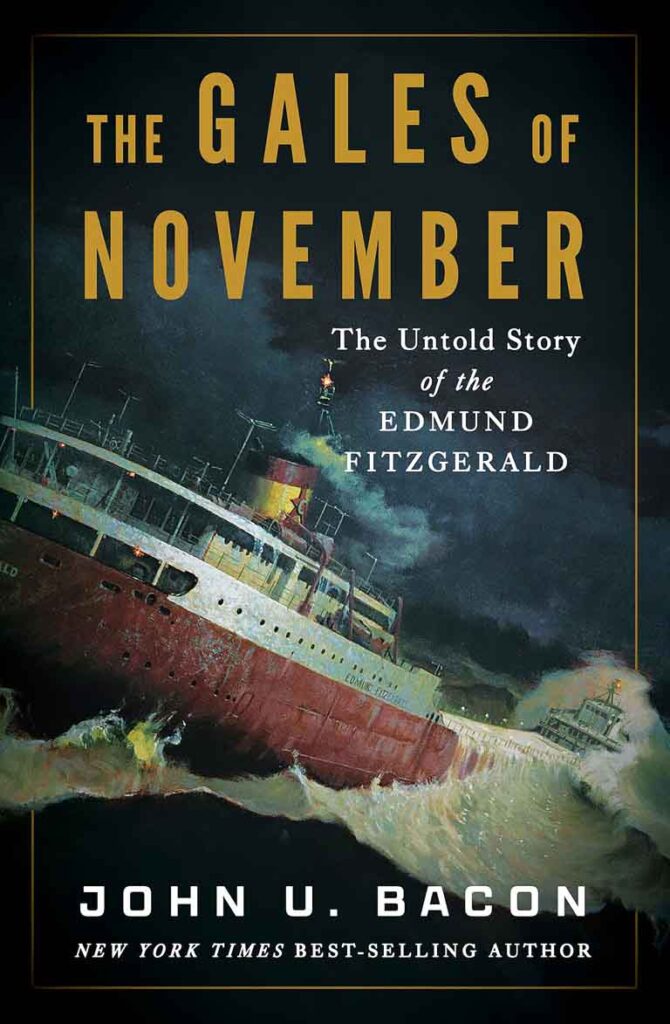

Between 1875 and November 10, 1975, 6,000 ships sank in the Great Lakes. Since then there have been no nautical disasters. This is what the research John U. Bacon uncovered while writing his New York Times Best Selling book, The Gales of November: The Untold Story of the Edmund Fitzgerald.

“One a week for a century and that’s the low number. Some say 10,000, some even say 25,000. It’s a stunning figure,” said Bacon.

In the 50th anniversary year of the sinking of the great ship, Bacon took part in the Lightfoot Days Festival workshops at Creative Nomad Studios with members of the Lightfoot Band, and he said the sinking of the Edmund Fitzgerald caused many things to change regarding shipping on the Great Lakes. Better weather reporting, better search and rescue, better mapping, a change of mindset among ship captains from the old, ‘we can tough it out,’ mold to, ‘storm’s coming, better seek shelter,’ no longer overloading vessels as was rampant back in the day, better inspections of ships and better shipbuilding are some of the things that contributed to 50 years of sailing on the Great Lakes with no ships lost.

When the Edmund Fitzgerald launched from the shipyards of Great Lakes Engineering Works of River Rouge, Michigan (Detroit area) on June 23, 1958 it was the largest and fastest ship on the lakes.

“It was one of the most powerful, one of the fastest and it was the best,” said Bacon.

It left Superior, Wisconsin for Detroit at 2:15 p.m. November 9. The SS Wilfred Sykes left the same port two hours later. The Edmund Fitzgerald caught up to the Arthur M. Anderson which had left Two Harbors, Minnesota earlier in the day on its way to Gary, Indiana. People from both of those ships would be instrumental in helping to figure out what happened to the Edmund Fitzgerald.

The day had turned to the 10th and they all encountered a storm at about 1 a.m. All three left the standard shipping route and headed toward the Ontario shoreline hoping to minimize the pounding they were taking. The Fitzgerald was already in trouble and was unable to make the same kind of headway the other two ships did. The last radio transmission from the Edmund Fitzgerald to the Anderson was at 7:10 p.m. They had all endured 18 hours of the worst weather imaginable.

“I have a chapter in there, The Storm of The Century 1913, it wasn’t. This was truly the storm of the century,” Bacon said.

There have been books written about the sinking, and of course Gordon Lightfoot wrote The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald. Bacon told the workshop audience Gord’s song made the sinking the second most well-known maritime disaster in the world after the Titanic. News organizations, particularly those in the Great Lakes area mark the occasion annually. In fact this writer and Bacon were listening at the same time each year to JP McCarthy’s morning-long special broadcast from WJR in Detroit, which featured several playings of Gord’s song and the church bells at Mariners’ Church in Detroit ringing 29 times, once for each member of the crew.

Bacon didn’t want to rehash what others had already written about. He wanted to tell the story of the people. He found family members of crew members and people who had been crew members of the Fitzgerald.

“What drove me was not to figure out what happened. It’s the 6 crewmen I got and the 14 families I got to. That, I think, drives the story. It’s very much what Gordon Lightfoot started with his song. It’s not just the industry, not the economics and so on, or what happened that night; it’s the people on the ship. That’s what I really wanted to get into.”

“We’re batting a thousand with them, knock on wood. It’s finally being told the way they want it told. That’s a relief; they trusted me with their stories. These people have never talked to a reporter before.”

The shipping season was to have ended the week before and two regular crew members could not make the extra voyage. Because of the extra week, Master Captain Ernest McSorley’s retirement did not begin on time.

“This trip was a tacked on. It was supposed to stop the season the week before. He had one more trip before his captain’s bonus to pay for his wife’s medical care,”

Bacon is a sports writer and broadcaster from Ann Arbor, Michigan (he has dual citizenship) who has authored 14 books including The Greatest Comeback: How Team Canada Fought Back, Took the Summit Series, and Reinvented Hockey; The Great Halifax Explosion: A World War I Story of Treachery, Tragedy, and Extraordinary Heroism; and Cirque du Soleil, The Spark: Igniting the Creative Fire that Lives Within Us All. Seven of his books have now reached the New York Times Best Sellers list.

The Halifax interest began with stories from his grandfather who lived in New Brunswick. As a sports writer, several of his books have been about University of Michigan athletics and Bacon had a little anecdote about a tie between U of M hockey and the Halifax Explosion.

“The first coach was a survivor of the Halifax Explosion as a first responder. That’s what turned him into a medical school student at Michigan and while he was there he started the Michigan hockey program,”

He, like many who grew up on, or close to The Great Lakes knows the story of the Edmund Fitzgerald, you almost can’t escape it. But to reach the best sellers list you need an audience larger than that.

“The publishers backed it completely. It’s also a big confirmation that what we are doing here is not just 50 years old, it’s still current, people are still interested. To be number six on the list, you can’t get mid-westerners, 60-year-old dads like me, you have to get 30-year-olds, you’ve got to get women, you have to get people in the Pacific Northwest. Its confirmation this story is not regional and it’s not demographically oriented. People are still fascinated.”

It took a long time for this story to become the next work.

“20 years ago my agent said no; got a new agent and five years ago he said yes,” said Bacon. He spent four years researching and interviewing in order to write the 110,000 word story. That included to trips from Marquette, Michigan to Detroit, and Duluth to Toledo, one each on the Arthur Anderson and the Wilfred Sykes.

Research into a subject can unearth information one might never consider, and interviewing the people who worked the ships revealed something different.

“Probably the most shocking fact is that commercial sailing on the Great Lakes are more dangerous than on the Atlantic Ocean. I wouldn’t have believed it, until I heard it ten times from guys who worked on both the Atlantic and the Great Lakes. Salt water smooths the waves out, spreads them out and the storms are a thousand miles away. On the Great Lakes the waves are sharp, pointy, close together and the storm is right on your end.”

This means riding waves bow and stern on the Great Lakes can leave a significant amount of ship, the middle, out of the water. Draw your own conclusions.

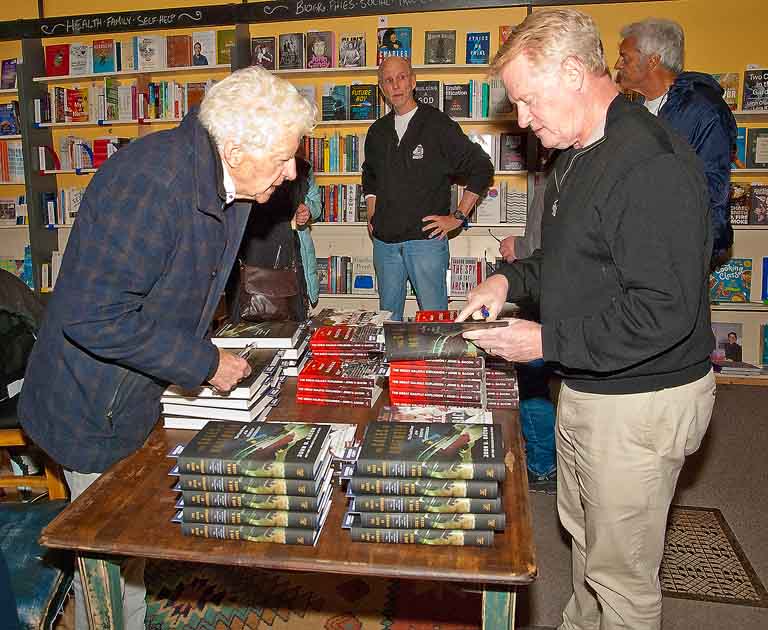

Bacon and several members of the Lightfoot Band spent Saturday morning of the festival at Manticore Books signing copies of both the Edmund Fitzgerald and Halifax Explosion books. There were a few stacks of them and it’s likely you can still pick up a signed copy.

(Photos by Swartz – SUNonline/Orillia and Images Supplied) Main: The Edmund Fitzgerald, (photo by By Greenmars, CC BY-SA 3.0)